Painted screens were a major

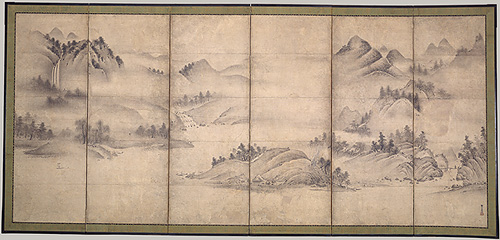

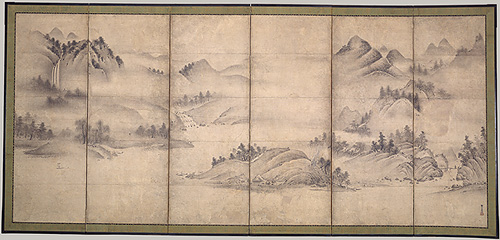

Landscape of the Four Seasons, Muromachi period (1392–1573), early 16th century

Kangaku Shinso (Soami) (Japanese, died 1525)

Pair of six-fold screens, ink on paper; 68 1/4 x 146 in.

|

component of traditional Japanese architecture, and their decoration reflected the leading schools and movements in Japanese art. They served many purposes, being used for tea ceremonies, as backgrounds for concerts or dances, and as enclosures for Buddhist rites. Like many artists’ studios, the traditional Japanese house lacked permanent walls, thus the screens became an architectural necessity, dividing up space, blocking drafts or lights, and serving as mobile decoration.

By the late 19th century, the importation of oriental screens to European cities seems to have catalyzed the adaptation of the concept by Westerners. The introduction of screens to the West was particularly well-timed, as it corresponded to a period of revived interest in decorative arts in interior decoration. Eventually, folding screens became a feature in any well-appointed setting.

Pierre Bonnard, 1867-1947

Nursemaids' Promenade, Frieze of Carriages, 1895

Four-panel color-lithographic screen

|

Numerous major European artists collected screens, and many others were so inspired by the form they created their own including many painters Ben Solowey admired such as Corot, Cezanne, Bonnard, and Whistler. The vogue for Japanese style objects resulted in commissions for Monet and Renior to create decorative folding screens.

Ben Solowey had an admiration of Japanese art and objects. He collected and displayed Japanese woodcuts in his home and studio. His

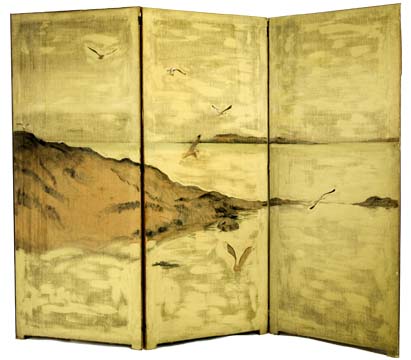

Casco Bay Folding Screen was created after his trip to the Maine coast in the summer of 1930. This “honeymoon” month-long excursion resulted in a number of fine paintings of the rocky coastline. Ben even took a number of photographs of the Bay’s ubiquitous seagulls.

Upon returning to his Fifth Avenue studio he soon conceived of creating a folding screen inspired by the Maine landscape. While he painted at least two large watercolors and divided the compositions into three sections, the final folding image bore only slight resemblance to these studies, not only in content but in the style of painting. Ben painted directly on linen in an approach that suggests both a Japanese dry brush effect, and Modernist simplicity.

The challenge of a folding screen is how one breaks up the composition among the folds of the screens. Ben featured a rocky outcropping on the left that runs over two panels before dissipating by the third. In the background of the center panel an impression of an island appears stretching over to the right panel. Seagulls in flight are scattered throughout. Ben abstractedly worked the linen to give the illusion of both sky and water, without actually painting either. The screen’s folds accentuate the breaks in the horizon line, carrying the eye further back into space.

Ben understood that once a screen divides an interior space, it changes from a two dimensional object to a three dimensional one. As such, it soon became a feature in his paintings in his New York studio. Soon after its completion, Ben posed Rae seated in front of it for a large oil portrait. It would later play a recurring role in a series of watercolor and ink figurative works in 1933 – 1934.

In 1935, the screen makes a cameo appearance in what is now one of Ben’s best known works

Rae Seated

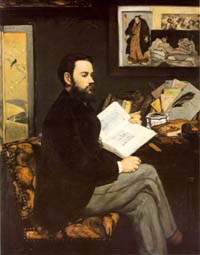

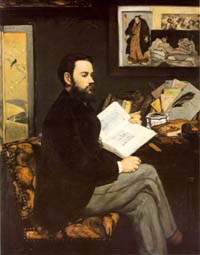

Portrait of Emile Zola

Edouard Manet, 1868

Oil on canvas, 146 x 114 cm

|

(Green Dress) at the Michener Art Museum. On the left margin of the work, a strip of the screen can be seen running from top to bottom. Perhaps it suggests Manet’s use of the edge of a screen in his portrait of Zola. Like that painting, the Solowey portrait, also featured the artist’s own work in the upper right corner of the image, and perhaps not surprisingly, both are painted in the artists’ studios.

A year later, the Soloweys purchased their farm in Bucks County, and much energy and time were devoted to the property until they moved there permanently in 1942. The Casco Bay Screen did not come with them, but was left in Rae’s sister’s apartment which would serve as the Soloweys’ New York pied-a-terre for the next four decades. There it provided the couple of measure of privacy when visiting.

Ben conceived another painted screen based on the myth of Leda and the Swan. He created several maquettes but ultimately unsatisfied he never brought the idea to life. His only other painted screen was for his rustic 1765 farmhouse. In keeping with the colonial flavor of the home and the furniture he made to go in it, he made a faux naïve screen with simple floral decorations. This was for privacy in the guest room right outside the Soloweys’ bedroom.

In the late 1950s Ben acquired a decorative linen screen which he frequently featured in his paintings and drawings from his studio. Sometimes as an object in the studio, and others as background for his still lifes.

Like so many other aspects of his work, Ben did not feel the need to add commentary to his folding screens. He considered it perfectly natural for him create this type of decorative project. Like the screen made by Cezanne’s screen, which served both a specific pictorial purpose as well as a functional one, reappearing in the background of several of his paintings, Ben’s was a private object. Although he never exhibited the work, we are pleased to present the piece, fully restored, alongside the works that inspired it, as well as the works it was featured in.

THE FOLDING IMAGE

The Interesting Life of a Painted Screen

September 27 – October 19

Free Opening Reception: September 27

The Studio of Ben Solowey

3551 Olde Bedminster Road Bedminster, Pennsylvania 18910 • 215-795-0228

Hours: Saturdays and Sundays, 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. from September 27th through October 19th. Other times by appointment.

Admission: $5; Free with invitation