Artist Simon Mauer tells of his unique Ben Solowey experience:

My wife Susan and I have had many pleasant and enriching visits to the studio of Ben Solowey, and as artists we particularly appreciate Ben’s skill in so many media. His work always has genuine beauty and often a poetic quality which charms the beholder. I am always attracted particularly to his charcoal drawings of which he was a master. I have often thought as I looked transfixed at them “if only I could go back in time and get a lesson from Ben; what knowledge I could gain!â€

One day at a recent visit to the Studio it occurred to me: why not ask if I could copy one of Ben Solowey’s charcoal drawings, surely there would be something to learn there! After all, copying has been a common means of learning from past-masters for centuries. David invited me in and I was, as always upon entering the studio, somehow changed, as if in a hallowed place; the smell of the old linen canvases and oil paints beguiling me, putting me in a state of mind receptive to aesthetic experience. After swinging my gaze around the room trying to mentally absorb the whole scene, appreciate all the beauty of the paintings and sculptures, the furniture and other artist’s accoutrements, I looked at a few of the charcoal drawings and in short order found one that was particularly striking; a dramatic likeness of Walter Huston in the role of Othello. This was irresistible. I set up an easel and my drawing board.

David was kind enough to show me as many of Ben’s charcoal sticks, and other drawing supplies as he could find… the lesson had begun. There were many boxes of charcoal … willow and vine… what, no compressed? Ah, he found one box hidden away. These were handsome old boxes made by manufacturers many of whom are long since defunct or still present in name only:  Rich Art, J.M.Paillard, Grumbacher.  But, as could have been predicted, (in spite of the claim “scientifically formulated†on the box of compressed charcoal) there were no special tools or magic drawing supplies made with secret recipes… Ben’s drawings are extraordinary, his tools were not.

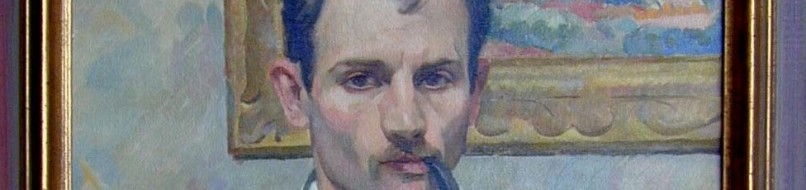

Soon David was called away and I was left alone in the old studio. I sat in front of my blank paper studying Ben’s magnificent

drawing on the easel next to me. I looked up and there high on the wall was Ben’s self-portrait looking down at me. I hadn’t noticed that I had set up right there. As I looked up at his likeness I wondered: was he looking down in approval?  Or could there be a trace of derision?  No, I felt assured his was a friendly visage, a kind and generous soul, a “kindred spirit†looking down as I began drawing.

The first aspect of Ben’s drawing that struck me was the pristine mark-making: I could find no stray lines or smudges, no evidence of an initial blocking-in, no false starts. I think this is evidence of a careful and highly skillful draftsman who made sure his drawing, which was going to be reproduced in the newspapers, was as clear and “legible†as possible. Another noticeable feature was the completely consistent quality of the darkest values he massed-in. As I attempted to achieve this property, I found I would press hard and try to layer the strokes but this destroyed the tooth of the paper leaving a streaky gray and black instead of an even dense black as Ben had made.  Any subsequent strokes of the charcoal would be ineffectual. I have not figured out yet how he did this. I thought perhaps he used compressed charcoal for the darkest darks, (I used only willow sticks for my copy work) but upon experimenting later with this I am not convinced this is the answer. I will keep working on this riddle. Perhaps it is simply a matter of a very skillful manipulation of the charcoal. Perhaps there was a magic material?  I doubt it; I tried a couple of Ben’s sticks and found nothing supernatural.

The modeling of forms in the Solowey drawing was less enigmatic but no less beautiful. I believe he used his thumb and fingers to blend the half tones, (David told me he would make a patch of charcoal at the bottom of the paper and pick this up with his thumb to use as needed for his half-tones), as is also common practice, he used a kneaded eraser to bring out his highlights, but all this was done with consummate skill and subtlety. His drawing shows a satisfying balance of bold expressive tone-masses, deftly modeled half-tones in the face, and lyrical line work especially in the detail of the costume. The effect is dramatic as suites the subject. Another key to the success of the drawing is Solowey’s flawless draftsmanship; this is the secret to capturing the expression and likeness of his thespian model’s face and gesture. More than any other aspect of realistic art correct drawing of proportion is necessary for achieving a likeness and for conveying the personal expression of the subject. It is not enough to have splendid handling of materials without form when doing a realistic portrait. Solowey’s drawing has both.

I spent about two and a half hours trying to copy Ben’s picture. What lessons did this reveal?  Firstly, that there is more for me to learn about the medium of charcoal. I remember my father once telling me that the most important thing he learned in college was that he didn’t know everything; and so it is that learning never ends. There is excitement in that realization. I look forward to trying to discover how Ben made those amazing black tones! Secondly I learned that there is power not just in expressive gestural mark-making but also in conscientious, careful, “legible†work. This quality helps make a drawing like Ben’s hold up even when viewed from across a room.  Thirdly I learned that some fundamental elements of a good realistic drawing; draftsmanship and composition, can be copied and they can possibly be learned with diligent practice, but the expressive individual line-making of an artist can only be mimicked to a degree. As I tried to duplicate Ben’s expressive marks I could not. His marks, which were made in a spontaneous gesture, could not be imitated using intentional calculated movements. But besides this, except as a learning experience there is no point in trying to mimic another artist’s style.  As an artist, should one not allow their expressive qualities to develop naturally, as their own? Or one could make an intentional effort to go against his or her own tendencies for ones own reasons. But why make an intentional effort to imitate another artist? Of course, most artists start out thinking about the work they admire and trying to make their work similar to it, but this eventually is replaced by ones own vision and handcraft. I think I see this in Ben’s work, a few influences from other great artists but in the end a gentle poetic voice of his own. Perhaps this is the most important lesson from Ben.