The trip that launched both the Solowey marriage and this exhibition was the Soloweys’ summer-long “honeymoon” to Casco Bay, Maine. it surely was a heady time for the couple and it inspired Ben. In our new exhibition there are three views of the same rocky promontory in Casco Bay. The photograph is Ben’s own contact print. The watercolor and oil turn the landscape

in a Cezanne-like abstraction. The rocky outcroppings along the shore would find their way into the Casco Bay Folding Screen.

in a Cezanne-like abstraction. The rocky outcroppings along the shore would find their way into the Casco Bay Folding Screen.

Same Scene, Different Media

Sep 28th, 2008 by David Leopold

Two Presidents at Solowey Studio

Sep 20th, 2008 by David Leopold

Two great American presidents will be appearing at the Solowey Studio during the run of our new exhibition. In honor of the Election Season, oil portraits of both John F. Kennedy and Franklin D. Roosevelt by Ben Solowey will be on view.

Studio during the run of our new exhibition. In honor of the Election Season, oil portraits of both John F. Kennedy and Franklin D. Roosevelt by Ben Solowey will be on view.

Also included is a 1936 campaign poster for Congressman Guy Swope, who would later serve as a Director in the Dept. of Interior under Roosevelt and acting Governor of Puerto Rico.

There is also campaign material for Bucks County State Rep. Jack Renninger from the late Sixties and early Seventies which featured a striking charcoal portrait by Ben.

Learn more about the Roosevelt portrait in The Letter. Come to the Studio to learn the stories of how the other politicians came to be immortalized by Ben Solowey.

Learn more about the Roosevelt portrait in The Letter. Come to the Studio to learn the stories of how the other politicians came to be immortalized by Ben Solowey.

Ben and Rae Solowey were lifelong Democrats and believed in voting in every election. We hope you do to.

Unfolding the Screen

Sep 14th, 2008 by David Leopold

Painted screens were a major component of traditional Japanese architecture, and their decoration reflected the leading schools and movements in Japanese art. They served many purposes, being used for tea ceremonies, as backgrounds for concerts or dances, and as enclosures for Buddhist rites. Like many artists’ studios, the traditional Japanese house lacked permanent walls, thus the screens became an architectural necessity, dividing up space, blocking drafts or lights, and serving as mobile decoration.

Painted screens were a major component of traditional Japanese architecture, and their decoration reflected the leading schools and movements in Japanese art. They served many purposes, being used for tea ceremonies, as backgrounds for concerts or dances, and as enclosures for Buddhist rites. Like many artists’ studios, the traditional Japanese house lacked permanent walls, thus the screens became an architectural necessity, dividing up space, blocking drafts or lights, and serving as mobile decoration.

By the late 19th century, the importation of oriental screens to European cities seems to have catalyzed the adaptation of the concept by Westerners. The introduction of screens to the West was particularly well-timed, as it corresponded to a period of revived interest in decorative arts in interior decoration. Eventually, folding screens became a feature in any well-appointed setting.

Numerous major European artists collected screens, and many others were so inspired by the form they created their own including many painters Ben Solowey admired such as Corot, Cezanne, Bonnard, and Whistler. The vogue for Japanese style objects resulted in commissions for Monet and Renior to create decorative folding screens.

were so inspired by the form they created their own including many painters Ben Solowey admired such as Corot, Cezanne, Bonnard, and Whistler. The vogue for Japanese style objects resulted in commissions for Monet and Renior to create decorative folding screens.

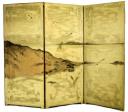

Ben Solowey had an admiration of Japanese art and objects. He collected and displayed Japanese woodcuts in his home and studio. His Casco Bay Folding Screen was created after his trip to the Maine coast in the summer of 1930. This “honeymoon†month-long excursion resulted in a number of fine paintings of the rocky coastline. Ben even took a number of photographs of the Bay’s ubiquitous seagulls.

Upon returning to his Fifth Avenue studio he soon conceived of creating a folding screen inspired by the Maine landscape. While he painted at least two large watercolors and divided the compositions into three sections, the final folding image bore only slight resemblance to these studies, not only in content but in the style of painting. Ben painted directly on linen in an approach that suggests both a Japanese dry brush effect, and Modernist simplicity.

The challenge of a folding screen is how one breaks up the composition among the folds of the screens. Ben featured a rocky outcropping on the left that runs over two panels before dissipating by the third. In the background of the center panel an impression of an island appears stretching over to the right panel. Seagulls in flight are scattered throughout. Ben abstractedly worked the linen to give the illusion of both sky and water, without actually painting either. The screen’s folds accentuate the breaks in the horizon line, carrying the eye further back into space.

Ben understood that once a screen divides an interior space, it changes from a two dimensional object to a three dimensional one. As such, it soon became a feature in his paintings in his New York studio. Soon after its completion, Ben posed Rae seated in front of it for a large oil portrait. It would later play a recurring role in a series of watercolor and ink figurative works in 1933 – 1934.

In 1935, the screen makes a cameo appearance in what is now one of Ben’s best known works Rae Seated (Green Dress) at the Michener Art Museum. On the left margin of the work, a strip of the screen can be seen running from top to bottom. Perhaps it suggests Manet’s use of the edge of a screen in his portrait of Zola. Like that painting, the Solowey portrait, also featured the artist’s own work in the upper right corner of the image, and perhaps not surprisingly, both are painted in the artists’ studios.

be seen running from top to bottom. Perhaps it suggests Manet’s use of the edge of a screen in his portrait of Zola. Like that painting, the Solowey portrait, also featured the artist’s own work in the upper right corner of the image, and perhaps not surprisingly, both are painted in the artists’ studios.

A year later, the Soloweys purchased their farm in Bucks County, and much energy and time were devoted to the property until they moved there permanently in 1942. The Casco Bay Screen did not come with them, but was left in Rae’s sister’s apartment which would serve as the Soloweys’ New York pied-a-terre for the next four decades. There it provided the couple of measure of privacy when visiting.

Ben conceived another painted screen based on the myth of Leda and the Swan. He created several maquettes but ultimately unsatisfied he never brought the idea to life. His only other painted screen was for his rustic 1765 farmhouse. In keeping with the colonial flavor of the home and the furniture he made to go in it, he made a faux naïve screen with simple floral decorations. This was for privacy in the guest room right outside the Soloweys’ bedroom.

In the late 1950s Ben acquired a decorative linen screen which he frequently featured in his paintings and drawings from his studio. Sometimes as an object in the studio, and others as background for his still lifes.

Like so many other aspects of his work, Ben did not feel the need to add commentary to his folding screens. He considered it perfectly natural for him create this type of decorative project. Like the screen made by Cezanne’s screen, which served both a specific pictorial purpose as well as a functional one, reappearing in the background of several of his paintings, Ben’s was a private object. Although he never exhibited the work, we are pleased to present the piece, fully restored, alongside the works that inspired it, as well as the works it was featured in.

The Solowey Story Continues to Unfold

Sep 11th, 2008 by David Leopold

The Studio of Ben Solowey is pleased to announce a new exhibition, THE FOLDING IMAGE: The Interesting Life of a Painted Screen, featuring a 1930 folding screen by Ben Solowey (1900 – 1978), and including paintings, drawings, and photographs that inspired it and works it was featured in. The exhibition will open to the public on Saturday September 27th at the Solowey Studio in Bedminster, PA with a reception from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. The installation will continue Saturdays and Sundays, 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., through October 19, 2008.

Ben Solowey’s talent continues to reveal itself. Acknowledged as one of the region’s great painters and sculptors, his hand crafted frames have been featured in museum exhibitions; his studio which he designed and created remains the envy of artists; and his handmade furniture that fills his home and studio continues to delight visitors. “Add a Japanese folding screen to the list,” says David Leopold, The Director of the Studio of Ben Solowey. “This object is unlike anything else in his body of work both in conception and style, yet is also quintessential Solowey in that it speak both to his artist and craftsman sides, as well as his deep knowledge of both Eastern and Western art. We are thrilled to show this work for the very first time.”

THE FOLDING IMAGE: The Interesting Life of a Painted Screen is the first exhibition to feature this unique six foot high, almost eight foot long folding screen. The exhibition also includes many never before exhibited paintings, drawings, and photographs of Casco Bay, Maine which served as the inspiration for the folding screen. “It is a relatively unknown period of Ben’s work,†says Leopold, “but it had a special resonance for Ben and his wife Rae, because that is where they spent their month-long honeymoon in 1930.†In addition there are works that feature the folding screen. “these work date from the early 1930s and reveal an intimate view of the Soloweys.â€

“The screen makes a cameo appearance in what is now one of Ben’s best known works Rae Seated (Green Dress) at the Michener Art Museum,†writes Leopold in an accompanying essay. “On the left margin of the work, a strip of the screen can be seen running from top to bottom.†Macquettes for other screens will also be on view

“With our Second Studio devoted to the folding screen,†says Leopold, “Ben’s main studio will feature a new installation of Solowey oil paintings, drawings, and sculpture.â€

The Peignoir Series

Jun 20th, 2008 by David Leopold

In the early 1960s, on an overnight visit to New York, Rae discovered that she had forgotten her dressing gown. Her sister, Rick, with whom Ben and Rae were staying, offered her one she had just purchased.

From the moment Rae slipped the peignoir on, all three realized it was something special to see Rae in it. Her sister never wore the peignoir again, as it returned with Ben and Rae to the Studio where Ben did a series of at least 10 watercolors of Rae wearing the peignoir. In each work, Rae is seen from the back looking into a mirror.The piece seen here is simply titled “Peignoir” and shows Rae in studio in front of Ben’s full length mirror in front of the studio windows.

In Water & Light, we have two examples of these acclaimed works, including one that hung in the Solowey bedroom for years.

One day we hope to mount an exhibition of these works, but for now this is your chance to see this particular obsession of Ben Solowey.

Look for the Studio in the Press

Jun 20th, 2008 by David Leopold

Our new show, WATER & LIGHT: The Watercolors of Ben Solowey, is a hit with what we refer to as the three C’s: Critics, Crowds and Collectors.

Our new show, WATER & LIGHT: The Watercolors of Ben Solowey, is a hit with what we refer to as the three C’s: Critics, Crowds and Collectors.

This Sunday there will be a nice review of the exhibition in The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Next week, The Bucks County Courier Times and The Intelligencer are publishing a big feature on the Studio and our current show. The photographer was out on a beautiful day, so there are sure to be some lovely new images of the Studio.

Discover Hidden Treasures

Jun 10th, 2008 by David Leopold

There will be more than watercolors in our new exhibition. For the first time in thirty years, visitors will see a striking portrait of a dear friend of Ben and Rae Solowey: Viginia Widenmeyer (nee Castleton).

Virigina was a writer living in the area who met the Soloweys through her husband. Ben and Rae so enjoyed her company that the publicity-averse Rae even consented to participate in an interview with Virginia on her beauty secrets for Prevention magazine! And it was Virginia who Rae turned to write a piece on Ben for the 1979 memorial exhibiton of Ben’s work at the Woodmere Art Museum.

Since her time in Bucks County, Virginia has led a peripatetic life and in her eighth decade she decided that she could no longer carry all of her beautiful objects of art with her wherever she goes. She contacted the Studio and sent two beautiful pastel still lifes (one in a Solowey handmade frame) and her portrait to be included in this exhibition.

What You Will See

Jun 5th, 2008 by David Leopold

There are landscapes, portraits, figurative pieces, and still lifes in our new show, WATER & LIGHT: The Watercolors of Ben Solowey, covering a nearly fifty year period.

Almost exactly sixty four years from our June 7th opening you could have seen the same work Spring Flowers – Iris & Daisies at the opening of the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual watercolor exhibition. Ben’s floral painting hung alongside works by Charles Sheeler, Edward Hopper, Diego Rivera (an old neighbor of Ben’s from New York), and Reginald Marsh to name a few.

There is also a classic example of a spontaneous watercolor inspiring a series of related works. “Evening,†a watercolor (top), turned to “Storm,†and oil painting passing through stages as a drawing and an etching.

“Evening,†a watercolor (top), turned to “Storm,†and oil painting passing through stages as a drawing and an etching.

“One of the most rewarding things in life,†writes critic John Russell on artist’s sketchbooks, “is to look over the shoulder of a great artist and see exactly what is going on.†Ben delighted in using pen, pencil or brush to record a quick observation or to study a composition that he might eventually use for a more accomplished painting. We have two sketchbooks with exquisite watercolors that provide us a revealing view of Ben at work, capturing the essence of the world around him.

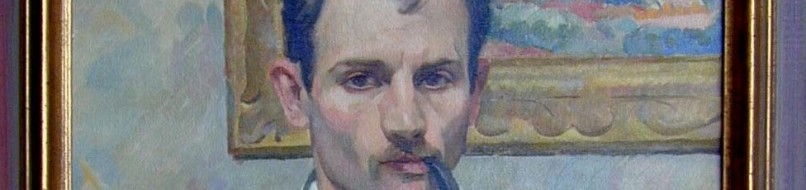

There are three self portraits in the exhibition, including the classic Self Portrait at Modeling Stand where shows himself sculpting with Rae seated nearby in the studio with a landscape and still life also on view. it is as complete a resume as Ben ever created.

Manet called still life ”the touchstone of the painter,” and this show includes several beautiful ones. Al of the flowers seen in these works were culled fromthe garden right outside the studio.

See Ben Solowey In A New Light

May 9th, 2008 by David Leopold

WATER & LIGHT: The Watercolors of Ben Solowey, the ultimate collection of works in watercolor, casein, and gouache by Ben Solowey will open to the public on Saturday June 7th at the Solowey Studio in Bedminster, PA with a reception from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. The installation will continue Saturdays and Sundays, 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., through June 29, 2008.

ultimate collection of works in watercolor, casein, and gouache by Ben Solowey will open to the public on Saturday June 7th at the Solowey Studio in Bedminster, PA with a reception from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. The installation will continue Saturdays and Sundays, 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., through June 29, 2008.

Acknowledged in his own day as an original and independent watercolorist, Ben Solowey had an intuitive relationship with this challenging yet flexible medium. A staple of his career, watercolors, and related media such as casein and gouache, were also his classroom, a way for him to learn through experimentation—with color theory, composition, materials, optics, style, subject matter, and technique, “far more freely than he could in the arena of oil painting,” says David Leopold, The Director of the Studio of Ben Solowey.” This exhibition provides an intimate look at how one of region’s most celebrated painters discovered for himself, over a period of more than five decades, the secrets of the watercolor medium.”

WATER & LIGHT: The Watercolors of Ben Solowey is the largest exhibition of Solowey’s watercolors ever to be presented. It features more than 40 rarely exhibited watercolors from the Solowey Studio’s collection that tells the story of Solowey’s development as an artist, presenting an intimate look at his watercolor practice, his techniques and materials, and the way he adapted his approach and his color palette to the many different environments in which he painted, from the quiet interior of his studio to the violent weather of an approaching storm. Throughout are works of his wife and primary model, Rae Solowey from soon after they first met and married through four decades of their life together.

The exhibition also examines the way Solowey’s watercolors relate to his work in oil and other media, revealing the central role the medium played in helping him to achieve the fresh, direct and beguiling scenes that have become his most enduring legacy to American art.

“With our Second Studio devoted to landscapes,†says David Leopold, Director of The Studio of Ben Solowey, “Ben’s main studio will feature a new installation of Solowey paintings, drawings, and sculpture.â€

Leopold’s Latest: Hirschfeld on Shaw

Apr 7th, 2008 by David Leopold

Studio Director David Leopold’s latest project is a unique installation for the Shaw Festival celebrating Al Hirschfeld’s drawings of George Bernard Shaw’s productions in america over seven decades.

Over those seven decades, Hirschfeld saw most major Shaw productions on and off-Broadway. Beginning with the Theatre Guild’s Major Barbara (1929), Hirschfeld captured the quicksilver of Katharine Cornell’s Candida (1937, which Ben also drew), Orson Welles’ Heartbreak House (1938), Ingrid Bergman in Captain Brassbound’s Conversion (1972) and more than 30 other performances. Perhaps no other artist documented Shaw in America as thoroughly as Al Hirschfeld.

productions on and off-Broadway. Beginning with the Theatre Guild’s Major Barbara (1929), Hirschfeld captured the quicksilver of Katharine Cornell’s Candida (1937, which Ben also drew), Orson Welles’ Heartbreak House (1938), Ingrid Bergman in Captain Brassbound’s Conversion (1972) and more than 30 other performances. Perhaps no other artist documented Shaw in America as thoroughly as Al Hirschfeld.

Shaw and Hirschfeld both had lengthy active careers, great capacities for work, and wore beards. Hirschfeld’s modern calligraphic portraits, combining his journalistic eye and wit, not only show us what the productions look like, but they give us the essence of the performances through his distinct point of view. “My contribution,†Hirschfeld wrote, “is to take the character — created by the playwright and acted out by the actor — and reinvent it for the reader.”

Hirschfeld tried to convince Moss Hart that Shaw’s Pygmalion was not going to be improved with songs and dance…just as the playwright/director began work on My Fair  Lady. But soon Hirschfeld was literally drawn in as his poster art captured both the spirit of the show and its original author. “…Shaw up in the clouds, manipulating Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews on strings, like marionettes,†as a priest in Paul Rudnick’s 1994 comedy, Jeffrey describes the drawing. “It was your parents’ [cast] album, you were little, you thought it was a picture of God. As, I believe, did Shaw.â€

Lady. But soon Hirschfeld was literally drawn in as his poster art captured both the spirit of the show and its original author. “…Shaw up in the clouds, manipulating Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews on strings, like marionettes,†as a priest in Paul Rudnick’s 1994 comedy, Jeffrey describes the drawing. “It was your parents’ [cast] album, you were little, you thought it was a picture of God. As, I believe, did Shaw.â€

This installation and the banners throughout the Shaw Festival theaters and the main display in the Triggs Production Centre are selections from more than sixty years of Shaw as seen by Hirschfeld. They provide the opportunity to appreciate the work of two theater legends and their immortal lines.