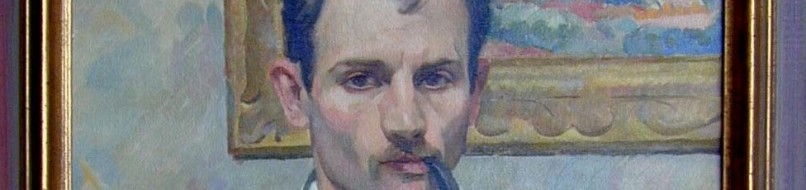

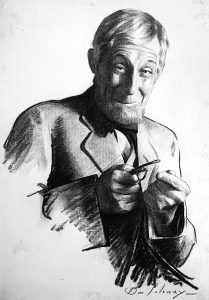

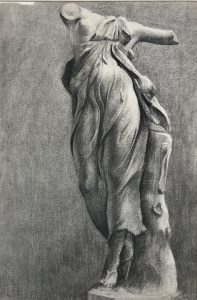

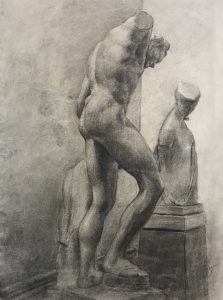

Ben Solowey won many awards while enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Right from the start, his Ramborger Award-winning drawing of an Academy charwoman was reproduced in the school’s catalogue in his sophomore year. Nevertheless, he did not win a Cresson scholarship, which provided at least $1,000 for study abroad.

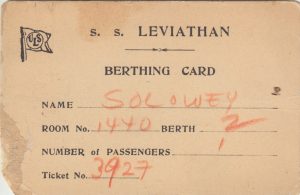

Undaunted, he got a copy of the Cresson checklist, and had it annotated by someone who had previously gone before and got a job as steward on the SS Leviathan, one of the largest and fastest cruise liners in the world.

The Leviathan had been built as the SS Vaterland in 1913 for the German Hamburg American Line, which incidentally was the same shipping line that Ben had come to America only ten years earlier from Russia. When World War I broke out, the Vaterland was docked in the neutral United States. When the U. S. entered the war in 1917, the Hamburg American’s Hoboken facility was seized by the American government and retrofitted as a troop ship that would eventually have a capacity of housing 14,000 troops. Its fast speed allowed it to crisscross the Atlantic without escort ships.

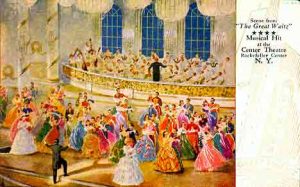

After the war, with a government surplus of ships, the vessel was leased to the United Staes Line who modernized the ship. The decorations and fittings, designed by New York architects Walker & Gillette, retained much of their prewar splendor of Edwardian, Georgian, and Louis XVI styles. They now merged with modern 1920s touches. The biggest deviation was an art deco night club supplanting the original Verandah Café. It returned to transporting civilians in 1923 to and from Europe for a minimum of five Atlantic voyages per year.

After the war, with a government surplus of ships, the vessel was leased to the United Staes Line who modernized the ship. The decorations and fittings, designed by New York architects Walker & Gillette, retained much of their prewar splendor of Edwardian, Georgian, and Louis XVI styles. They now merged with modern 1920s touches. The biggest deviation was an art deco night club supplanting the original Verandah Café. It returned to transporting civilians in 1923 to and from Europe for a minimum of five Atlantic voyages per year.

Although he traveled in third class, Ben spent his days crossing the Atlantic is the nicer parts of the ship. It made for a stylish arrival for the young artist to Europe.