For more than 25 years I have both literally and figuratively looked over the artist’s shoulder as he/she works at an easel. That’s what curators do. We want to see not only what the artist has created, but when possible, how they did it, what was their motivation, and what was the context. Sometimes it feels like putting together the pieces of a puzzle, with the best result being a complete picture with every piece in its place. This rarely happens because…a wide range of reasons. Most artists rarely keep detailed diaries of why and how they are working and memories are faulty or circumspect. An artist can have reasons why a work was created and ten years later look at the same work and see a different set of reasons. 25 years or more, the artist may have different reasons then the first two proffered. It isn’t that the artist is lying, it is simply human nature to see things differently as we get distance from them. Curators try to provide the history and context of a chosen work for an exhibition or publication from extant evidence, but rarely are in the studio while the artist works to observe and ask questions.

During the run of our last exhibition, Leaving a Mark: Second Annual Works on Paper Exhibition, we invited Paul DuSold to return to the Solowey Studio to present one of his celebrated portrait demonstrations. Visitors may remember that in 2010, during the run of a joint exhibition of Solowey and DuSold paintings here at the Solowey Studio (one of the two times we have showed a contemporary artist’s work here), Paul made history by painting the first work in the studio since Ben Solowey’s death in 1978.

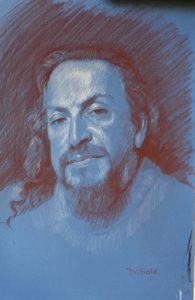

Paul is one of the few accomplished portrait painters who not only can capture the personality of his sitter, bu t also speak intelligently to an audience while doing it. In his first demonstration, he worked in oils before a rapt audience. This time we asked if he would draw rather than paint in honor of the exhibition. He agreed, a date was set, and a model was engaged. As the day approached, our model was unable to make it. I called someone else, but they were unable to come, so as the morning broke, I realized that since my wife and son were unavailable or unwilling, I would take the chair on Ben’s model stand and sit for Paul.

t also speak intelligently to an audience while doing it. In his first demonstration, he worked in oils before a rapt audience. This time we asked if he would draw rather than paint in honor of the exhibition. He agreed, a date was set, and a model was engaged. As the day approached, our model was unable to make it. I called someone else, but they were unable to come, so as the morning broke, I realized that since my wife and son were unavailable or unwilling, I would take the chair on Ben’s model stand and sit for Paul.

I was to have done that once before, in the fall of 1978, when my twin brother John and I were to have sat for a portrait by Ben himself. In the family, when one approached the age of 13, someone—frequently Rae’s sister Rick—often commissioned Ben to draw a portrait. My late sister Ann had sat for a lovely pastel portrait at the age of only eight, and my older brother Matthew had sat for a charcoal drawing at 13. Rae would later tell me that Ben was looking forward to drawing my portrait and John’s because he could not tell us apart, but he knew that once we sitting in front of him our distinct personalities would make it clear who was who. Unfortunately, Ben died three months before the portrait was to have been drawn. At the time, it was of little consequence, but over the years and my deepening involvement with all things Solowey, I regretted that we were denied the experience of sitting for Ben.

Now 38 years later, on a lovely fall day on the farm, I climbed the steps of

the model stand in Ben’s studio to finally sit for a portrait. Instead of the crème colored Strathmore paper that Ben used for his charcoal drawings, Paul pulled out a blue paper. As he would explain during the demonstration, he likes to work on a colored paper because it allows him a wide range of values in both light and shadow, whereas charcoal on essentially white paper limits an artist to working on the shadows. Paul asked me to look right at him, so that the final portrait would meet the eye of the viewer. In our social lives we rely on cues from a person’s face to understand what they are saying or thinking, and we naturally respond. In this case, I held the gaze of Paul while he looked right through me and around me, and while he squinted, grimaced and concentrated on his drawing, I had to remind myself not to react but to remain as placid as a face on Mt. Rushmore.

the model stand in Ben’s studio to finally sit for a portrait. Instead of the crème colored Strathmore paper that Ben used for his charcoal drawings, Paul pulled out a blue paper. As he would explain during the demonstration, he likes to work on a colored paper because it allows him a wide range of values in both light and shadow, whereas charcoal on essentially white paper limits an artist to working on the shadows. Paul asked me to look right at him, so that the final portrait would meet the eye of the viewer. In our social lives we rely on cues from a person’s face to understand what they are saying or thinking, and we naturally respond. In this case, I held the gaze of Paul while he looked right through me and around me, and while he squinted, grimaced and concentrated on his drawing, I had to remind myself not to react but to remain as placid as a face on Mt. Rushmore.

I occasionally allowed my eye to wander to the audience who thankfully were not looking at me, but rather at the portrait that Paul seemed to pull from the paper. A number of artists were present, and many had technical questions, which Paul answered succinctly and calmly as he drew. Paul discussed what he was looking for in his subject and how he was attempting to capture it. It was a fascinating conversation for non-artists, because we too often concentrate on the façade of the subject and think in terms of emotion, while the artists are often thinking about the light and how to describe it in their chosen medium. In many ways the portrait subject is rarely that important. Had it been a beautiful woman sitting for Paul he would have drawn her in a similar fashion. The finished work would have looked different of course, but the intent would have been the same.

My wife was concerned that I may not be able to sit still long enough to have my portrait drawn, but I did my best to remain immobile and quiet. This also gave me insight into how Rae may have felt when she sat for Ben in the studio. My mind did wander, but I was intent on holding my pose. I even asked Paul several questions during the sitting. After only 90 minutes (with one short break), Paul completed his portrait sketch. As one who had only looked an artist and his work from one side of the easel, it was illuminating to be on the other side and see how the artist looks and reacts as he works.

We are indebted to Paul DuSold for providing such a unique experience. It deepened my appreciation for Paul’s work (you can see more at pauldusold.com) and provided a better understanding of what goes into a portrait.